- Home

- Sam Gayton

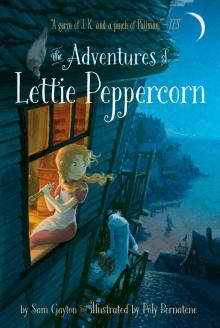

The Adventures of Lettie Peppercorn Page 9

The Adventures of Lettie Peppercorn Read online

Page 9

“It’s a sing-song shrub,” Noah explained when he saw her staring. “I brought it with me when I left home.”

She imagined him living here in this room. It was easy. Everywhere there were little touches showing his kindness and caring—things she knew already. But the cabin also revealed things she didn’t know: how messy he was, and how lonely. She thought of him afloat and alone on the wide, wide sea, with no family or friends. How he must miss his home. Why else would he bring a singing plant from the fifth continent? Lullabies at bedtime, of course.

“Right,” said Noah, snapping her from her thoughts. “Water’s boiled. You’ll be all defrosted in no time.”

He fetched a blanket, a hot-water bottle, and a thermometer. He draped the blanket around her, but it went stiff and shattered. The hot-water bottle froze as soon as he put it by her feet. He stuck the thermometer under her tongue, but the red bar wouldn’t even budge past the lowest temperature (which was -50˚). Lettie groaned and spat it onto the floor.

“Nothing’s helping!”

“I’ll boil some more water,” said Noah. “You just worry about getting warm.”

“I am worrying about getting warm!” she snapped. “Sorry. I just did it again.”

Noah shrugged and his stalk shook as his shoulders came down. “Guests are allowed to be grumpy.”

“Only the ones who have paid,” she mumbled. “I’m not meaning to be nasty, Noah. I’m just scared.”

There was a little silence. Even the Wind was still.

“Four drops is a lot of æther,” he said quietly.

“Oh, Noah,” said Lettie. She fought back tears, because they would only freeze in her eyes. “I don’t think I can stand it! I might stay cold like this for months, or years.”

“I don’t think so,” said Noah. “Because I make very good soup.”

“What should I do?” asked Lettie.

“Wait there,” said Noah. “And try not to sneeze.”

Then he chopped two onions (diced), three garlic cloves (sliced), and a sweet potato (grated).

Lettie watched:

“Bring it to the boil slowly, Noah.”

“That’s a lot of garlic, Noah.”

“Don’t grate your thumb.”

Noah grew some peas and split the pods over the pan. He stepped back from the stove, leaving the soup to simmer.

“Just one more thing to add, to make it spicy,” he said, wiping his brow on the back of his hand.

“Pepper?” suggested Lettie.

“Something more special than that.”

“Oh.” Lettie frowned. “What then? Not ginger. I hate ginger.”

Noah clenched his fists and screwed his eyes shut. Blood rushed to his face and his forehead shone with sweat. He shook, he gasped for breath. A green stem grew from his stalk, and on the end of the green stem hung a tiny, flame-red chili.

He picked it and held it gingerly, as if at any moment it might burst into flames. “A Blazing Pip, it’s called. The hottest thing I can grow. Let me ladle up a bowl for myself first. Then I’ll add the Pip . . . and you can eat. You must be hungry.”

“I’m nothing but cold, cold, cold.” She sat in the chair, feeling like a grandma.

“You won’t be cold much longer.” Noah crushed the Blazing Pip and Lettie felt a ripple of heat through the air that made her eyes prickle. He dropped it in her bowl, and brought it over with a spoon to where Lettie sat.

“Eat it quick as you can,” he said. “While it’s hot.”

“I’ll sip slowly, Noah. It’s good manners not to slurp.” She brought the soup to her lips and took a sip.

“Feel anything?”

“Just cold.”

Noah looked nervous. “Try gulping.”

Lettie slurped a bit more, and now she could feel something tingling on her tongue, like tiny bubbles. She took another spoonful, and the bubbles started in her stomach too. “What’s happening?” she cried anxiously.

Noah smiled back. “It’s working.”

Lettie’s face began to soften slowly, slowly, into a huge smile. “I can feel it, Noah! My stomach is warm, oh! I can’t tell you how wonderful it feels. Tingly and crackly!”

She dropped the spoon, tipped back the bowl, and slurped the rest of the soup down.

“Who cares about good manners!” she said, thrusting the bowl into his hands and letting out a gigantic burp, low and long as a ship’s horn.

“Lettie!” said Noah, mouth open. “You’re defrosting!”

She laughed out loud—even if she was a little embarrassed—and white steam flew from her lips.

“I can feel it,” said Lettie, putting her hands up to her face. “Oh, I can feel my cheeks again! Thank you, Noah! That soup was really, really hot.”

“It’s my specialty,” he said proudly.

“It’s boiling and bubbling. I think it’s spreading down my arms! And there’s something building up in my head too . . .”

Just then she heard a high hissing noise.

“Is that more steam?” she said as Noah began to laugh.

“That’s right,” Noah told her. “It’s coming out your ears . . . Now it’s coming out your nose!”

Lettie could barely hear him above the hissing that had now risen to a whistling. “I’m glad you’re laughing!” she shouted, putting on a pretend frown. “My head’s a kettle!”

She’d spent a whole morning without any warmth, and now she was piping hot. It was a wonderful feeling.

“Let’s just hope you come off the boil soon,” said Noah, a touch of worry in his voice.

But Lettie could already hear the whistling fade, and as it did she was reunited with her whole face again: eyes, ears, mouth, and nose. All her old friends. It was good to have them back.

“Oh, I need a handkerchief,” she said, her eyes and nose streaming. “Everything’s runny! Quick!”

She wiped away her tears and blew her nose hard on a leaf that Noah yanked from his stalk. They were tears of happiness at being safe and alive. She was warm right down to her toes, and utterly exhausted. She couldn’t help but close her eyes. Noah’s smile was like the crescent moon. The sing-song shrub hummed a lullaby.

“How do you feel?” asked Noah.

“Tired.”

He asked her a hundred other questions—about what the crones had said, about how she had come up with the plan—but that was the only one Lettie remembered answering.

Where the Wind Blows

Lettie woke to the salty smell of more soup on the stove. She sat up and groaned. “What time is it?”

“Late enough for supper,” Noah said. “You slept for the whole day.”

Lettie looked through the porthole, at the darkness.

“Is Blüstav still out there?” she asked.

“Course he is. I had to give him a gas lantern, though. He says he doesn’t like the dark.”

“Serves him right for everything,” said Lettie, and flopped back in her chair.

“How do you feel?”

“Like one big bruise.”

“Eat,” he commanded, handing her a bowl of broth and gray shells.

“Only if you tell me what it is.”

“Clam soup,” he said proudly. “Another of my specialties. Even Blüstav enjoyed it!”

“Blüstav.” Lettie scowled at the mention of him. “You fed him too, did you?”

“I had to,” chuckled Noah. “He can’t feed himself with that cloud under his coat. He spilled most of the soup, but he managed a clam or two.”

Lettie looked down at her bowl. The clams didn’t look very tasty, but it would be rude not to try. She scooped one from its shell and chewed. It was hot, salty, and delicious. She sipped the broth and sighed with happiness.

“Thank you, Noah. They’re delicious.”

He laughed. “All part of the service!”

She laughed too. “You shouldn’t have let me sleep so long, though!”

“I couldn’t wake you,” said Noah. “You

were dreaming deep, saying things.”

“Was I?” Lettie felt herself turn red. “What things?”

“Mostly mumbles,” said Noah, going over to his desk and sifting through the maps. “Then you started talking about your ma.”

“Oh,” said Lettie. “So it was a good dream.” She cursed herself for not being able to remember it.

“You said, ‘The first rule of alchemy is: Things change,’ ” Noah told her. “Here it is!” He found the star map he wanted and rolled it up.

Lettie nodded. “That sounds like something my ma would say to me. I suppose it’s true. But can things ever change back, Noah?”

“Course they can!” he said, stopping to look at her. “You took æther; you were colder than anyone’s ever been before. But now you’re fine again.”

“Thanks to you.”

“What else do you want to change back, Lettie?”

She took a deep breath, because what she wanted to say next could only be said in the simplest of words and she had to make sure that Noah understood them.

“I just want to see Ma, and for it not to be a dream.”

Noah nodded and waited for her to carry on.

“I want to see the inn and Da back to normal too, but I’m at sea now and everything seems so far away.”

“I know.”

“Will I ever see the inn again?”

His eyes shone. “Yes.”

“What about Da? Will I ever see him back to normal?”

“Yes.”

“And what about Ma?”

“Yes, Lettie. You’ll see her.”

Lettie smiled. Somehow, Noah saying it made her sure that it would happen. Then she bit her lip. “But when? Where?”

Noah took a gas lantern, stuck the map under his arm, and shrugged on his coat. “Where the Wind blows, of course.”

“What does that mean?”

“That’s where we’ll find her. Wherever the Wind takes us to, that’s where she’ll be.”

“But . . .” Lettie threw her hands in the air, struggling with the strangeness of it all. “Noah, we’re wandering off into the ocean, led by a breeze!”

“What’s so odd about that? When you’re sailing the sea, that’s all you can do. If the Wind wants us to travel this way, then we will.”

He took her bowl and put it in the bucket with the others. “I’m going outside, to see if I can work out which direction we’re headed.”

“What should I do?” said Lettie.

Noah shrugged. “Relax.”

The cabin door creaked open and shut, and she was alone.

“I’ll tidy up,” said Lettie, looking around. “This place is a mess.”

But before she started on the cabin, Lettie had to tidy up herself. She was a mess too. She took off her shoes and socks for the first time since leaving Barter. Somehow, the muck and grit of the town had got into her shoes, and now her feet were filthy.

She went to the water bucket, wet a cloth, and scrubbed them hard. Nothing happened. Her feet stayed speckled with gray.

Worry crept up on her. She scrubbed them again. Again.

“What’s happened?” Saying the question aloud scared her even more.

Perhaps she should use soap. Maybe the grit and grime was just caked on. Perhaps she was just imagining things.

“No, I’m not,” she said to herself. She wasn’t imagining, she was petrifying! Her feet weren’t dirty; they were turning to stone, just like Periwinkle. Pulling on her socks and shoes, quick as she could, she sat on the bed breathing hard.

“I should never have left the inn,” she whispered. “I shouldn’t have done it!”

There was something in the ground that Ma had warned about in her note. It was real. And Lettie hadn’t listened, and now this . . .

Lettie Peppercorn, you think about something else.

But she couldn’t. Whatever was happening scared her, and there was not a lot of good being scared when she was on a tiny wooden boat in the middle of the sea, miles from home.

She willed herself to be calm. Last night her feet had petrified, but now she was miles away from Barter, so it couldn’t happen anymore. She was safe.

Wasn’t she?

“Lettie Peppercorn!” she hissed. “Stop worrying and do something useful.”

So she did the washing up. It helped to take her mind off her feet, at least. Scrubbing the dirty bowls, Lettie’s thoughts returned to Periwinkle, and she realized how much she missed him. She’d got so much to tell him about: snow, her trip across the sea, and her new friend Noah. She ended up talking to Da instead, still on the shelf above the stove.

“Noah’s messy like you, Da. Just look. But he does make very good soup.”

Lettie looked up at Da, and thought of him back on the jetty. She’d assumed he was just babbling nonsense, but maybe there had been some sense in him that night.

“I’m sorry I broke my promise to you, Da. Is this what touching the ground does to me?”

Da just sat on his shelf, being a bottle.

“Well,” she said. “I hope you’re happy. I can look all the way to the horizon now and there’s no ground in sight.”

She stacked the plates, made the bed, and watered the sing-song shrub. After that she paced about, still feeling restless. Lettie was not used to being a guest. She wasn’t sure she liked it. She was only a guest because of Noah: on Leutha’s Wood, he was in charge. He knew how to steer and how to tie complicated knots and rig sails. Lettie realized with sudden shock that she hadn’t any jobs left. She decided at once that she would march outside to Noah and demand to be given one.

But then she stopped.

Lettie Peppercorn, what on earth are you doing?

This was the first time in her life that she didn’t have to look after anyone but herself! No guests to serve! No Da to scold! No Peri to feed!

She felt lighter. She felt excited. She was on an adventure, and she felt twelve years old not twelve hundred, for once.

“What shall I do with myself?” said Lettie. “I’ll go and look at the stars, that’s what!”

But before she did, she whispered to Da that even though she was stonesick and homesick, anxious and scared, there was something else that shone through all the bad feelings. She was happy.

Outside, the night was very cold and clear as glass.

“I love the stars,” said Lettie, looking up. She felt herself swaying along with the ship. “You can look up at them and forget everything else.”

Noah was looking at the stars too. His constellation maps were spread across the deck and he had fastened them to the wood with thorns from his stalk.

“That’s what snow reminded me of, when I first saw it,” said Blüstav’s disembodied voice from somewhere above them. “Stars.”

“No, it didn’t,” snapped Lettie. “It made you think of diamonds, and getting rich. Why are you such a liar?”

“I’m not,” Blüstav lied.

There was something troubling Lettie. It was her nose. She could smell a saltiness in the air that set her on edge. What was it?

“I’ve something to tell you,” said Blüstav.

“Be quiet,” said Lettie, trying to concentrate on her nose. “I’m ignoring you.”

“Then you’re a fool, because it’s important.”

“Can you smell something?” she asked Noah, but he was immersed in his maps.

“I’ve just worked out our longitude,” he announced.

Lettie sniffed the salty smell again. It was still there, and getting stronger. It had a metallic tang that she could almost taste. She felt queasy. And why was she suddenly scared?

“What is that?” she said to herself.

“We’re north . . . ” answered Noah. “Way north.”

“We’re in whaling territory,” called Blüstav. “I said whaling territory.”

And Lettie realized what the smell was: blood.

It was the Bloodbucket!

“They’re out there!” she s

houted to Noah. “I know it! There’s blood and coal in the air. It’s the crones!”

“Are you sure?” Noah frowned. “It should’ve taken the Bloodbucket days to dig out of all that ice.”

“I think you underestimate their industriousness,” said Blüstav cheerfully. “If I were you, I’d let me down. Only my alchemy can defend you.”

Lettie felt her insides twisting. Blüstav’s voice had a gloating edge. Something wasn’t right here.

“He’s up to something,” she murmured. If only she could look at him she might be able to figure out what, but all she could see of the alchemist was a little glow, high up in the blackness.

“He’s trying to scare us,” said Noah. “We’re safe for now. They won’t find us in the dark.”

“Not unless they had a light to follow,” said Blüstav, holding his lantern high.

Something came out of the darkness toward them like a falling star.

THWUNK!

It hit the mast, embedding itself in the wood just above the sail—a harpoon with a rag of burning pitch wrapped around the shaft.

Lettie couldn’t move; she was hypnotized by the flames, paralyzed by terror. What should she do? Pull out the harpoon? Put out the flames?

“Time to let me down now!” sang Blüstav.

Then the sail caught fire. In seconds it was ablaze, and the deck filled with smoke, sparks, and the smell of burning. A second harpoon hit the cabin door. Noah yanked it from the wood and tossed it into the sea.

“We’ve got to get away!” Lettie shouted to Noah.

“How can we?” he called back. “We don’t have a sail!”

With a dreadful, drowning feeling, Lettie realized the Wind could no longer help them. They had no sail. They were on their own.

She searched frantically for the Bloodbucket. Somewhere out in that blackness, it lurked. Somewhere out in that blackness, the old crones watched them burn.

“They’ve snuck up on us, Lettie. They must have put out all their lights and engines, that’s why we can’t see or hear them.”

Lettie looked up at Blüstav, floating above the deck with his lamp shining in the night.

The Last Zoo

The Last Zoo His Royal Whiskers

His Royal Whiskers Lilliput

Lilliput Hercufleas

Hercufleas The Adventures of Lettie Peppercorn

The Adventures of Lettie Peppercorn