- Home

- Sam Gayton

His Royal Whiskers

His Royal Whiskers Read online

For Pops, who is Tops

PART ONE

Catastrophica

I came, I saw, I conquered.

—JULIUS CAESAR

Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong.

—SOD’S LAW

(A NOTE ON NAMES)

This is a tale from Petrossia, a land far from where you or I sit now. The king there is called the Czar, which is pronounced “zar.” The stories say it was actually spelled zar once too, but that was before he decided to wage war on the letter C and force it to join his name. After a long and ferocious battle, C was eventually defeated, and the victorious zar told it to march as a herald at the front of his name forever.

The letter C had to obey.

But it wasn’t going to cheer about it.

So now you know why, when you say the Czar’s name, the C is silent.

1

Bad News at Breakfast

Bloom and Swoon and many a moon ago, in the lands beyond the Boreal Sea, there lived a mighty king who loved conquering. He conquered crowns and cities and countries. His name was the Czar.

Conquering was the Czar’s favorite hobby. He practiced all the time, so he was really rather good at it. He could conquer a whole kingdom guarded by ten thousand soldiers using nothing but a tin whistle, a fishing rod, and a herd of reindeer.1

He was a terrifying beast of a man—broad as a bear, strong as an ox, clever as a pig, and hairy as a goat. His burgundy boots shone, his midnight cloak swished, and his Iron Crown sat slowly rusting on his head. He could crush coconuts with his hands and do push-ups with his mustache. He was simply the mightiest conqueror of all time. Everyone agreed. And if you didn’t, the Czar would fight you until you changed your mind.

One bleak morn at the end of Dismember, the Czar woke late and sat down to conquer his huge breakfast of twelve ostrich eggs. He cracked the shells first, one by one. It was his favorite part. He liked imagining they were skulls.

He dipped all his buttered soldiers, gobbled them up, then called the butler and demanded toasted reinforcements.

The butler left to inform the cooks. After a while, the doors to the chamber crashed open. On a velvet cushion by his elbow, the Winter Palace poodle wagged his tail and sat up, as the maids marched up from the kitchens, carrying a whole new battalion of toast that was buttered on both sides.

“Down, Bloodbath,” growled the Czar, jabbing the poodle with his fork. “My breakfast.”

But the Czar and his poodle were surprised by another visitor along with the maids. It was one of the Czar’s War Council. And he was carrying bad news.

The Czar’s War Council was made up of five of his most powerful soldiers—and surely the bravest and toughest of them all was his Warmaster, the barbarian warrior Ugor, who stood before him now. Ugor had fought in every single one of the Czar’s conquests. He had been slashed with swords, stabbed with spears, and recently poked in the eye with a chopstick.2 But the Czar had never seen him look so afraid before. Ugor’s unbandaged eye was filled with fear as he announced that a terrible catastrophe had befallen the Czar’s six-year-old son and only heir—Alexander, the Prince of Petrossia.

“What do you mean, a terrible catastrophe?” scoffed the Czar, catapulting breadcrumbs out of his mouth and across the breakfast table. “Has my son been kidnapped? Ha! Kidnapping doesn’t worry me in the slightest, Ugor! I will simply invade any kingdom holding him to ransom.”

“No, Majesty,” grunted Warmaster Ugor, turning pale. “Badder than kidnap.”

“Worse than kidnapping?” cried the Czar. “You mean my son has been murdered? Then I must try to fulfill my ultimate ambition: conquer the land of the dead, and bring Alexander back from the afterlife!”

“No, Majesty.” Ugor’s knees were knocking together. “Badder than murder too.”

“Worse than murder?” cried the Czar, and even he began to feel a little afraid. “What has happened?”

But Ugor was so overcome with terror, he fainted and toppled with a thud to the floor.

With a scowl, the Czar booted Bloodbath out from under his ankles. The poodle scampered over to the Warmaster, licking and slobbering all over Ugor’s face until the barbarian regained consciousness. Finally, the Warmaster sat up and managed to inform the Czar that Prince Alexander, his only son and heir to the mighty Petrossian Empire, had somehow been transformed into a fluffy-wuffy kitten.

The blood of the Czar himself ran cold. “You mean to say that the heir to my great empire is now a . . . a . . .”

“Kitten,” confirmed Ugor with a groan. “And, Majesty?”

“What?” said the Czar in the barest whisper.

“He’s got fleas too.”

Even Ugor—Warmaster, and bravest of the Czar’s War Council—could not meet His Majesty’s smoldering stare of rage.

“How?” growled the Czar. “How did this happen?”

“A potion, Majesty,” Ugor said whilst hiding behind his beard.

“Alchemy?” The Czar clenched his fist until his knuckles cracked. “Who brewed and bottled it?”

“Two children,” said Ugor. “Boy and girl. Lord Xin catch them. Got them in dungeons now.”

“Assassins, no doubt. The Duke of Madri must have sent them on a revenge mission.” The Czar glared down at Bloodbath, who whimpered and hid under the table. “I never should have kidnapped his poodle.”

“Not assassins,” Ugor explained. “Just children. Living here in Winter Palace. Prince Alexander’s two best friends.”

The Czar made the sort of face—half surprised, half disgusted—that ramblers usually make when they fail to see the cowpat.

“My son has friends?” said the Czar. This was getting worse and worse.

“Best friends,” corrected Ugor.

“He has best friends?”

Ugor nodded. “Two of them.”

“TWO?!”

The Czar stood up and thumped the breakfast table with his fist. He thumped it so hard that his twelve ostrich eggs bounced up from their eggcups and cracked on the floor like guillotined heads. He swept the stacks of buttered soldiers off their silver tray. All fifty of them fell facedown on the bloodred carpet. In all the Czar’s life there had never been a greater proof of Sod’s Law.

“This is a disaster!” he roared. “Not only is my son a kitten, but a friendly kitten too? This is a CATASTROPHE. How can I have a fluffy-wuffy furball for an heir? How can he command an army when he can only meow? How can he hold a sword with paws? How can he be a conqueror? HOW?!”

The Czar roared that last question so loud, his voice echoed through the entire Winter Palace, as if searching for an answer.

“How?

How?

How?

HOW?”

It echoed off walls painted eggshell blue and windows fringed with white cornices, like icing on a cake . . .

It was heard across the courtyard, in the ears of all the marble statues that made up the Fountain of Sobs: a pyramid of kings and queens conquered by the Czar, whose chiseled effigies had been plumbed up to weep an endless splish of tears . . .

It went all the way up to the gilded chimneys on the rooftop, and all the way down to the kitchens in the basement, and even farther below that, to the dungeons. . . .

Where, behind a great many locked doors, down a great many torch-lit tunnels, and in a great deal of trouble, a boy and girl sat together, trying to think of a way out.

“We’re getting our heads cut off,” Pieter Abadabacus said when he heard the Czar’s cry echo down to them.

There in the gloom beside him, Teresa Gust shook her head. “You don’t know that for sure. The Czar might have been yelling angrily for a completely different reason. Maybe he stubbed his big toe.”

A

second roar of rage echoed down to them.

“Both big toes,” Teresa corrected.

Pieter gave her a look.

She shrugged. “It happens.”

“We never should have made that potion, Teresa!” Pieter slumped his shoulders, letting his heavy lead chains clonk onto the floor. “Poor Alexander. Poor us. What was I thinking?”

That was a question Pieter would never find the answer to. He was an Abadabacus; the thirteenth in a long line of master mathemagicians; a genius who had trained in Eureka and had (at the age of four and a half) single-handedly saved that city from being destroyed by the Czar.

He had lived in the Winter Palace ever since, serving in the War Council as Petrossia’s Royal Tallymaster. The Czar entrusted him with working out the most important of sums. Not only did Pieter know exactly how many men it would take to conquer North Hertzenberg (three legions, give or take a battalion), but he knew how many steps they would have to march to get there (two million), and the shoe size of every soldier in the company. He knew his fifty-seven times table, for infinity’s sake. . . .

So why, in the name of everything odd and even, had he been so stupid as to go along with Teresa’s idea?

“I’ve got some new escape plans!” she suddenly announced.

Pieter sighed. “Have any got a better chance of working than the eleven you’ve already suggested?”

Teresa gave him one of her looks (the one with the narrowed eyes and the scorn). “They had potential.”

“Infinitesimal potential.”

“I don’t see you coming up with any ideas.”

That was true. But then Pieter often left the brainstorming to Teresa. She was a completely different type of genius from him. His brain was all about answers—working them out, choosing one that was right, checking it over twice . . .

But Teresa Gust had Imagination. And Imagination was all about knowing what questions to ask in the first place.

“All right,” he told her. “Let’s hear your escape plans.”

“What if we brew another potion that turns iron into chocolate? Use it on the bars of this cell, nibble through them, and make a run for it?”

“We don’t have a cauldron,” Pieter pointed out. “Also, you hate chocolate.”

“We’ll dig, then,” Teresa suggested. “Find an underground river, and doggy paddle to freedom.”

Pieter gestured at his uniform. Unlike Teresa, whose suit was covered with grappling hooks and color-coded patchwork pockets, his Tallymaster uniform was a plain gray suit and cloak. It included a gold T for Tallymaster, embroidered on his lapels, and a left sleeve made out of paper, so he could jot down equations. It did not include a shovel. Or inflatable armbands.

“All right,” she said. “We befriend a mouse and ask it to steal the keys to the cell—like the old folkmother does in the Hansa and Greta story, when those two horrible children lock her up and start gobbling her home.”

Teresa looked expectantly over at a rat skulking round the corners of her cell. She gave it a friendly wave, and held out her hand for it to shake.

“I’m in the wrong fairy tale,” she huffed a moment later, sucking her bitten thumb.

Pieter had to agree. But despite everything, he laughed. How did Teresa come up with so many ideas? Where did they come from? And why did they never fail to make him smile? She was like a conjurer, drawing a never-ending rainbow scarf of notions from out of her sleeve. Even now, he could not help but shake his head in wonder.

That was the reason he was in this mess, Pieter worked out suddenly. That was why he’d started secretly brewing potions in the basement, and ended up turning Prince Alexander into a kitten. The answer was very simple:

Numbers were predictable.

Teresa Gust was not.

For example: they first became friends after she had kidnapped him.

* * *

1. This actually happened. On the first day of Bloom, the Czar had ridden north to the kingdom of Laplönd and challenged King Harollia to single combat.

Normally, of course, no king would accept such a challenge. It would be suicide. But the Czar had carried no weapons: only a tin whistle and a fishing rod.

So, arming himself with battle-ax and bommy-knocker, King Harollia accepted.

When he charged, the Czar climbed a fir tree and proceeded to play an irritating Yuletide tune very badly. The noise enraged a herd of nearby reindeer, who stampeded through the valley, sweeping King Harollia away. Up in his tree, the Czar used the fishing rod to pluck the crown from King Harollia’s head as the reindeer carried him past.

2. Last summer, when the Czar had surprised the Ninjas of Soy during breakfast and conquered them before lunch.

(A NOTE ON TIME)

We’re going back in time now, to the month when Pieter and Teresa first met. Perhaps it would have been simpler to start at the start, but this is a tale about two geniuses, and Pieter and Teresa have never in their lives done anything the easy way.

So, in your mind, see the days going backward. Imagine the brown Dismember leaves drifting upward, fixing themselves back onto the bare branches of the trees, growing green again and scrunching up into buds. Imagine the salmon of Swoon swimming north again, up the River Ossia, fish tails first, like silver needles unstitching the water. Imagine the smell of spring blossom, and the kitchen shelves creaking with the weight of apricots, artichokes, and chives.

Stop there. Don’t go back any farther than Bloom. Calendars in Petrossia are only seven months long. Spring and summer stick around for a month each, and autumn lingers for two, before a long winter comes howling down from the Waste in the north to swallow up the rest of the year. There is a rhyme the Petrossia folk tell their children, and here it is:

Springtime is Bloom,

Summer is Swoon,

Autumn is Sway and Dismember,

Winter is Welkin and Worsen and Yule—

I’ve told you, so now you’ll remember.

2

Pieter + Teresa = Trouble

One night in Bloom, three months past, before Dismember turned the leaves brown and the geese south and the Prince of Petrossia furry, Pieter woke up in the middle of the night and found he was not in his bed but in a large black sack.

“What’s going on?” he mumbled. “Where am I?”

His genius brain answered him at once with a few possibilities. Pieter chose the most statistically probable option.

“Somebody help!” he yelled. “I think I’ve sleepwalked into a garbage bag!”

(This happened more often than you might think. Pieter had a habit of pacing back and forth—both while he worked, and while he dreamed.)

From somewhere, he heard the creak of pulleys. The bag was winching slowly upwards. Hopefully this wasn’t the conveyer belt to the Winter Palace’s garbage incinerator.

“Help!” he called again.

“Quiet!” hissed a voice. “Aren’t you supposed to be a genius?”

“Aren’t you supposed to be helping me out of this garbage bag?” Pieter answered.

There was a sigh from outside. “Are you really a mathemagician? Because you sound like an idiot.”

(Like many of the finest mathemagical geniuses, Pieter could be either, depending on the subject.)

“Of course I’m a mathemagician,” he said indignantly. “Test me if you want.”

There was a pause. “What’s the square root of ninety one thousand, two hundred and four?”

“Three hundred and two,” Pieter answered.

“Umm . . . correct,” decided the voice. “Probably.”

Before Pieter could reply, the sack opened, and he was falling. He clonked onto a wooden floor and looked around with bleary eyes.

He was not in his tallychamber, with its dust and tinderlamp and endlessly multiplying spiders. There were no censuses, no records, no surveys around him. No stack of Tallymaster tasks, no stove where Pieter threw scrunched-up paper all scribbled with sums, no list detailing how many ho

rseshoes the Czar had in total (both lucky and unlucky).

Pieter was down in the palace kitchens, on one of the enormous shelves that rose up and crisscrossed each basement wall, like tree branches. It was a jungle down here. The air was a hot damp fog of spicy aromas and steam. Down on the floor below, orange fires purred in their stoves like sleeping tigers, while great swamps of porridge bubbled and burped in pans, ready for tomorrow’s breakfast.

But the cooks and the maids were all in bed. Pieter glanced down at the grandpapa clock ticktocking by the double doors. Its hands pointed at three of the morn.

“Took you down the chimney, in case you’re wondering,” said the voice. “All the fireplaces connect together. Hidden passages, if you think about it. Quick and secret. Not very clean though. Sorry about the soot, by the way.”

Pieter looked down at his filthy pajamas.

Then around at the girl standing behind him.

Being a genius, Pieter was used to figuring people out within a matter of moments. They were like puzzles he could solve. The Czar, for example, was clearly an evil tyrant with ambitions for world-domination (it was the mustache that gave him away).

The girl Pieter found himself face to face with, though, confounded him—like a sum that didn’t add up right. She was a short, plait-tailed serf in a coat made of pockets, yet somehow she equaled more than that. Pieter couldn’t solve the proud angle of her chin, or measure the length of her moon-white hair, or the depth of her eyes, the color of morn stars. Her smile was an enigma. It had suddenly appeared on her face, and he had no idea why. Nor did he understand why he found himself grinning along with her, as if she was an equation he had to balance out.

“Teresa Gust,” she said, thrusting her hand out. “Spice Monkey. Serf. And right now, I suppose, Kidnapper.”

“Pieter Abadabacus.” He took her hand and she yanked him to his feet. “Royal Tallymaster and Mathemagician.”

The Last Zoo

The Last Zoo His Royal Whiskers

His Royal Whiskers Lilliput

Lilliput Hercufleas

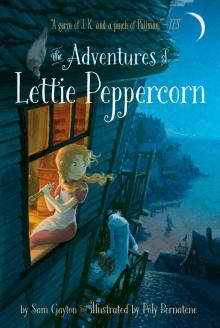

Hercufleas The Adventures of Lettie Peppercorn

The Adventures of Lettie Peppercorn