- Home

- Sam Gayton

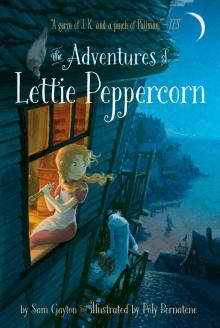

The Adventures of Lettie Peppercorn

The Adventures of Lettie Peppercorn Read online

PRAISE FOR

The Adventures of Lettie Peppercorn

“A tale of self discovery, family, and friendship . . . an inventive and accomplished debut.”

—Independent on Sunday

“Full of action and invention.”

—Sunday Times

“Full of fairy-tale and fun, which should appeal to Lemony Snicket fans.”

—Daily Mail

“Beautifully old-fashioned storytelling [which] weaves a hugely imaginative tale of alchemy, family, and snow.”

—Bookseller

“A most fantastical story, not dissimilar to Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland.”

—School Librarian

THANKS

FOR DOWNLOADING THIS EBOOK!

We have SO many more books for kids in the in-beTWEEN age that we’d love to share with you! Sign up for our IN THE MIDDLE books newsletter and you’ll receive news about other great books, exclusive excerpts, games, author interviews, and more!

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com/middle

To Erin, who is Boss.

“Of bodies changed to other shapes I sing”

Ovid, Metamorphoses

CONTENTS

A RECIPE FOR SNOW

1. A Stranger Arrives

2. An Invention Called Snow

3. Kicking Out the Breezes

4. One Boy Travels a Very Long Way

5. The Suitcase Opens

6. Lettie Peppercorn Brews Tea

7. The Making of the White Horse Inn

8. Follow Those Frostprints!

9. The Wind Lends a Hand

10. The Endless Inflation of Blüstav the Alchemist

A RECIPE FOR SNOW:

A never-before-seen meteorological phenomenon

Made with LOVE, ALCHEMY, and the following INGREDIENTS (listed in their order of use):

A length of silence, at least one hundred years long

Dust motes, charged with static

Seven drops of æther

Six dice

One teaspoon of salt

A string of frost, threaded through an icicle

A gray cloud, spun upon a silver wheel

Water

INSTRUCTIONS:

Cut the century-long silence into seven tiny moments.

Sprinkle the moments with dust and static.

Add a drop of aether to each.

Then throw in the dice (which ensures the snow remembers to have six sides). Repeat this six times (for luck).

Stir in a teaspoon of salt (so the snow will melt).

Sew everything inside the cloud, using the icicle needle and thread of frost.

Finally, add water.

A Stranger Arrives

On a winter night so cold and dark the fires froze in their hearths, snow came to Albion. It came packed up in the suitcase of a stranger. Lettie was the first to see him.

The stranger walked up from the harbor, dragging his luggage bump bump bump over the cobbles of Barter town, searching for the sign of the White Horse Inn. He found it on Vinegar Street, swinging from the porch of a house on stilts. Up above, through the little kitchen window, Lettie the landlady watched him come.

With her telescope, she traced the long line of footprints etched behind him in muddied frost. She saw him put a hand on the ladder that led to the door and start to climb, up through the black and swirly night. The Wind was so strong it could have whisked away the fingers from his hands, and he wore no gloves. It was the coldest winter Lettie had ever known, and he was by far the coldest guest.

His teeth were blue.

His hair was white.

His fingers were blue.

The whites of his eyes were blue, and his pupils were white.

“A man with an icicle beard,” she whispered to Periwinkle, who had just flown inside. “Where will we put him? All the beds are taken.”

Periwinkle cocked his head and Lettie sighed. For a pigeon, he was a good listener, but he was terrible at conversation.

Lettie closed her telescope with a snap and dropped it in her apron pouch. She went into the tiny front room, where her two guests—a Lady from Laplönd and a Bohemian jeweler—sat in armchairs by the hearth. Their real names were signed in the guestbook, but Lettie called them the Walrus and the Goggler. The Lady was the Walrus, because she was fat with whiskers. The jeweler was the Goggler, because she did nothing but stare. They suited Lettie’s names better than their own.

“Someone’s coming up,” said the tiny, shrunken Goggler. She hooked her scopical glasses around her ears and flicked down the lenses to glare at the door, her eyes big as saucers.

“He will not be having my bed,” said the Walrus. Her wobbly lipstick pouted, her piggy eyes squinted, and her treble chins shook.

Lettie had no time to answer before the door flew open. On the porch stood the man with the icicle beard.

“I need a room,” he said, “and it must be freezing!”

At once, the fire died down to embers. The Wind swept in, and before the Walrus could cover her ears, it snuffed out the ten tiny candles on her chandelier earrings.

“Yes,” said the stranger softly. “This will do nicely.”

His smile made a cracking sound, and a shard of his icicle beard fell to the floor.

Lettie stared. With jitters in her belly, she went to pick up his suitcase, but he shooed her with his hand.

“Get away,” he said with a scowl. “Far too delicate.”

“I’m not delicate,” she answered. “I’m twelve.”

“I was talking about my merchandise,” he snapped, nodding at the mahogany suitcase. “It’s very . . . sensitive. If it was spoiled, you wouldn’t want to buy it. And I would have come all this way for nothing.”

“Sir,” said Lettie. “I don’t know what you’re selling, but I can’t afford it.”

“Don’t be presumptuous,” barked the stranger. “I know a customer when I see one.”

The Walrus and the Goggler watched from underneath their furs.

Lettie was speechless. For a week she had heard nothing but:

“More sugar in the tea!”

“More blankets on the armchairs!”

“More wood on the fire!”

Now here was someone—a frozen man with a suitcase full of mystery—telling her that she was his customer.

Lettie Peppercorn, stop your gawping and say something, she thought.

“Welcome to the White Horse Inn, sir.”

“Yes, yes!” he said impatiently. “Now fetch the landlord before I defrost!”

Lettie rolled her eyes. New guests always made this mistake. She wiped her hands on her apron. “I’m the landlady.”

“You?” he sneered.

Lettie gave him one of her sterner looks. “That’s right, sir. Me. Lettie Peppercorn.”

“Well, what about Mr. Peppercorn?”

“Da’s at the pub, if I had to take a guess. Down by the harbor, at the Clam Before the Storm, betting with the sailors.”

The stranger pursed his blue lips in irritation. “And Mrs. Peppercorn?”

“Well,” said Lettie hotly. “If I had to take a guess, I’d say that’s none of your business.”

“Girl, you have no idea about my business. Remember that. You’re just a customer.”

“I’m much more than that,” said Lettie. “I wash sheets, I dust shelves, I tidy up rooms, and I brew a very good cup of tea.”

“Her talents as a landlady,” said the Walrus, “are satisfactory.”

“But the decor is atrocious,” said the Goggler, “and rather ugly on the eyes.�

�

Lettie followed the stranger’s gaze as it swept around the tiny room. The White Horse Inn was drab and bare. The pictures were gone from the walls, leaving dark squares on the wood. There was a dining table by the kitchen, two armchairs by the fire, and Ma’s old pianola in the corner. There was one rug left. It was small.

“It looks cold enough,” he said.

“But all our beds are full,” said Lettie.

“I don’t want a room for sleeping, girl. I want a room for business.”

Lettie was in half a mind to give him a lecture on good manners and send him packing. But she couldn’t. The White Horse Inn needed money. Da’s gambling already had Mr. Sleech, the debt collector, knocking at the door each week. So instead of a telling-off, she gave the stranger a smile and showed him her wide, wonderful eyes: the eyes of her ma, long gone.

“Certainly then, sir. Bed or business, it’s all the same rate here . . .” She stuck out her hand and said: “Three shillings a night, if you please.”

“Three shillings is reasonable . . .” began the Goggler.

“. . . for an inn with more than one rug,” finished the Walrus.

“You can have any room you like for your business,” said Lettie, ignoring them. Then she lowered her voice so the old ladies couldn’t hear, and added: “Even theirs.”

She expected him to haggle. He was a businessman, and this was the town of Barter, after all. But he just scowled and said, “I better get everything I need from you.”

“You will,” Lettie promised. “With a brew and a smile.”

“Very well,” he said. “We have a deal.”

Lettie had to stifle a cheer. She was so desperate for money that she would have taken two shillings. Three would cover all of Da’s debts for tonight. If she sent them to him now, he wouldn’t have to borrow from Mr. Sleech, the debt collector. And that meant that Mr. Sleech wouldn’t come around at midnight for the last rug.

Three cheers for the man with no manners and an icicle beard! she cried out in her head.

Lettie realized that she didn’t know his name. He hadn’t introduced himself, which was strange indeed, especially since he was a businessman and she was supposed to be his customer. She wondered if it would be rude to ask, but before she could he bent down suddenly and picked three pebbles from the black ice around his boots.

“Here,” he said. “Put out your hand.”

Lettie folded her arms instead. “Sir, I asked for three shillings, not stones.”

“And I said, ‘Put out your hand.’ So stop your pouting and do as I say, girl.”

Reluctantly, Lettie obeyed. He dropped the pebbles into her palm: one, two, three. Reaching inside his coat, he brought out a glass vial shaped like a J. It was filled with thick, silver liquid. He twisted off the cork and put a drop on each of the pebbles.

And something happened.

Something extraordinary.

The pebbles began to fizz. They jumped in Lettie’s palm like crickets.

“Keep them in your hand!” said the stranger.

Lettie clasped her hands together, and inside the pebbles bounced around. Then the air went pop! three times, and they fell still. A little wisp of smoke wriggled from between her fingers.

“Finished,” said the stranger, corking the bottle.

Lettie opened her hands.

She couldn’t help but gasp.

The old ladies in their armchairs just stared, openmouthed.

“Now,” the stranger said, “we can get down to business.”

But Lettie couldn’t. She was rigid with shock. In her palm the pebbles were gone, and in their place were three silver shillings.

“How did you do that?” she whispered.

He put the bottle away inside his coat. “An alchemist can make anything he wants.”

Lettie clutched the coins up in her fist. That word: alchemist. She hadn’t seen an alchemist for years. Now there was one at her inn, making money from rocks and carrying a suitcase full of mystery. . . .

The last alchemist to stay at the White Horse Inn had been Lettie’s ma. But she was gone now. She’d left three things: a note, her coat, and a hole that had never been filled.

“It’s a long time since we had an alchemist here at the White Horse Inn,” Lettie said to him as he fiddled with the straps around his suitcase. “The last one vanished through the window.”

“I shall be keeping the windows shut,” he said without interest.

“Did you know this inn was made with alchemy, sir? It started life as rubbish, rubbish that got mixed up in a cauldron with special alchemicals, and it all got changed and ended up a house—”

“I’ve no time for chatter!” he said, his temper sparking. “You’re to do as you’re told, or I’ll turn those shillings back into pebbles just as quick as I made them.”

Lettie scowled. “There’re rules for staying here,” she said. “The ledger’s over there, and you’ve got to sign it. Your name, where you’re going, and what you’re carrying.”

He strode up to the book, leaving frostprints as he went, and took the quill in his hand.

“Do you see his teeth?” murmured the Walrus.

“Bright blue,” said the Goggler, filling a pipe with mint leaf. “And do you see that suitcase?”

“Mahogany,” the Walrus said. She shivered and her chandelier earrings twinkled. “How unusual.”

“How interesting.”

Lettie rushed into the kitchen and took the room keys from the hook by the stove. Periwinkle fluttered on his perch, a message from Da dangling on his foot:

Nearly won the last game! Might borrow a few more shillings. Don’t worry; I’ve got a good feeling about this! Da xxx

Da always had a good feeling after a few bottles of beer.

Lettie put that thought out of her mind quickly, before more bad ones came.

“Borrowing a few shillings?” she murmured. “Not this time, you’re not!” She turned to Periwinkle. “I’ve got a message for you to fly back in a bit, Peri. But now I’ve got to settle in the new guest. He’s got a temper. He’s got blue teeth too. Let me find out his name for you.”

She went back into the front room with the keys. The alchemist threw down the quill and picked up his suitcase without a word. Lettie peered at the ledger to catch his secrets. Her eyes went wide when she saw where he had signed: the red ink had run blue.

Lettie looked at the quill, then back at the page.

He hadn’t signed his name at all.

It just said Snow Merchant.

Lettie wondered. A merchant was someone with something to sell.

But what was snow?

An Invention Called Snow

“What’s snow?” asked Lettie.

“You’re my customer,” said the Snow Merchant. “You’ll find out soon enough.”

There was expectation in his voice, like sparks. Lettie could tell he was excited. She could tell he was nervous.

Nervous about what? she wondered.

The Snow Merchant swung his suitcase up onto the table. Its legs creaked with the weight.

“I’ve never seen a suitcase made of mahogany before,” said Lettie. “And I see a lot of suitcases in this business.”

“It’s bolted and buckled with lead,” said the Snow Merchant.

“Must be hard to carry!” said Lettie.

“It keeps what’s inside weighed down,” he answered.

Lettie frowned. She had been landlady to dozens of guests, and they always brought with them one thing: luggage. There had never been a suitcase like this before. The prizefighters from Bavolga brought their leather boxing gloves, in search of new opponents; the chess players from Yssa brought their black-and-white boards, looking for new moves; the perfumers from Parall brought empty boxes, to catch new smells in . . . Lettie even knew where the Walrus was going next with her luggage: back to Laplönd with the Goggler, to show off the new chandelier earrings, which the Goggler had made.

But what ha

d the Snow Merchant brought with him? What was the mystery he wanted to sell to Lettie?

Suddenly the clock by the bar chimed ten, and the Snow Merchant jumped. “The coldest hour of the night will come soon!” he cried in panic.

Lettie tore her eyes from the suitcase. “Is that bad?” she asked.

“It means there’s no time!”

“No time for what?” said the Walrus.

“For the creation!” he said. “For the creation of snow! I have to make it before I can sell it, and to make it, I need a room!”

Lettie jangled the keys. “Which would you like, sir?”

“No, no!” the Snow Merchant cried. “There’s no time to choose!” He looked around. “This one right here will do!”

And before Lettie could stop him, he strode up to the hearth to do battle with the fire. It hissed and spat at him, as if the two were old enemies. The Snow Merchant regarded it contemptuously and then plunged a hand into his huge, black coat. He rifled away, searching for something. Lettie heard the rustle and clink of bottles as he went through each pocket.

“Here it is!” he cried, withdrawing a small, crooked vial with a pipette lid. He shook it in front of his eyes and watched the contents slosh inside the glass. To Lettie, it looked like liquid frost: bitter blue, cruel, and cold.

“Oh, yes,” he said, his voice soft with menace. “You know this, don’t you? It’s æther, isn’t it? And it shall be the death of you.”

The ladies in their armchairs whimpered, and Lettie quaked and backed away, but she realized that the Snow Merchant wasn’t talking to any of them: he was talking to the fire. Feeling rather foolish, she looked again to the flames as they squirmed in the grate.

The Snow Merchant unscrewed the lid and Lettie’s goose bumps rose. The æther leeched the warmth from the room.

“Quite hard to obtain,” said the Snow Merchant. “And quite impossible to bottle, but nevertheless, I am a genius.”

He squeezed the pipette and it sucked up a drop of æther.

He turned to Lettie. “You might want to light a lamp.”

“Why?” she asked, trembling. “What does æther do?”

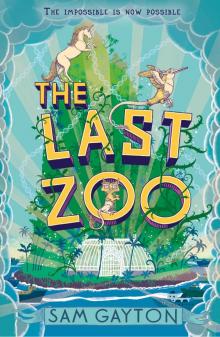

The Last Zoo

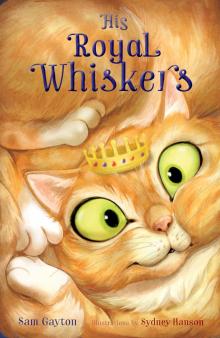

The Last Zoo His Royal Whiskers

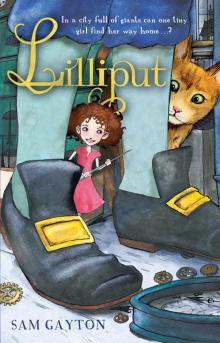

His Royal Whiskers Lilliput

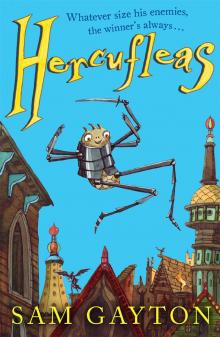

Lilliput Hercufleas

Hercufleas The Adventures of Lettie Peppercorn

The Adventures of Lettie Peppercorn