- Home

- Sam Gayton

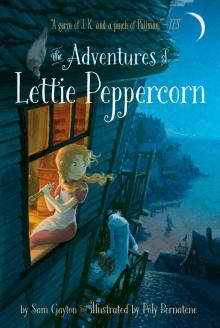

The Adventures of Lettie Peppercorn Page 7

The Adventures of Lettie Peppercorn Read online

Page 7

At once the Wind interrupted him with an angry gust.

He tried to carry on: “When we escaped from Petrossia I made her my apprentice and taught her everything I knew”—the Wind blew hard again, and Blüstav began to pirouette on his rope—“but then she betrayed meeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeEEE!!”

Blüstav couldn’t continue his story: the Wind wouldn’t let him. It gusted around him; it twirled him in the air like a weather vane.

“Stop it!” he begged, spinning round and round, his face a queasy blur. “Help me! Let me down!”

“Leave him alone!” Lettie scolded the Wind. “Let him speak!”

She started to pull Blüstav down out of the Wind, but Noah stopped her.

“It’s angry because he’s lying,” Noah said. “Not because he’s speaking.”

At once Lettie understood. Of course Blüstav was lying—to him it was as natural as breathing! Somehow, the Wind knew, and it was trying to shake the truth out of him. She should have known herself: his eyes were easier to read now that the æther was wearing off.

Lettie Peppercorn, you gullible fool!

“Right!” she shouted. “That’s enough!”

The Wind stopped. A whimpering Blüstav bobbed on his rope.

“I’m sick of lies,” said Lettie. “Sick! And if you lie again, I’ll let the Wind blow until you’re sick too!”

Blüstav’s mouth opened and closed, but he had nothing to say.

“Every time you bend the truth, every time you twist it, or spin away from it, the Wind will twist and spin you.” Lettie sat down on the deck and made herself comfortable. “And that’s how it’s going to be. For as long as it takes the truth to come. Understand?”

Blüstav nodded.

And he began slowly—for the first time in his life—to tell the truth.

The Making of Snow

Blüstav and Teresa met in an underground prison, somewhere in Petrossia. The prison belonged to the czar, ruler of that dark land of forests. They had both been sentenced to die in a horribly gruesome way, involving nothing but a teaspoon and two barrels of beetroot soup.

The czar had Blüstav in chains for “borrowing” alchemy books from one of his rivals, and “forgetting” to give them back.

Teresa had also committed a crime involving alchemy. She had changed the czar’s son, the Prince of Petrossia, into a cat.

“I saw him kick a dog on the street,” Teresa explained. “I thought the dog might like to get its own back.”

Blüstav was naturally suspicious of this brown-haired girl with fierce eyes. None of the alchemical books he’d ever “borrowed” had told him how to change a person into a cat. They were all about making gold. He decided that Teresa must be a liar, which made him uneasy. Being a liar himself, he knew how troublesome they could be. It was not until they were an hour away from their terrible execution that he realized Teresa was, in fact, telling the truth (which meant too that she was a genius).

They were chained by shackles of lead to a cold stone floor, listening to the dank walls drip, when Teresa turned to him and said, “You’re an alchemist, aren’t you?”

“The greatest now living,” lied Blüstav.

“I want to be an alchemist,” said Teresa. “I want to turn pebbles into pigeons and walnuts into whales.”

Blüstav naturally assumed that, as well as lying, Teresa liked to tell jokes. He laughed.

“Girl, an alchemist dedicates himself to one thing: turning lead into gold. Understand? An alchemist wants to become rich. Alchemy is the science of greed.”

“Well, most alchemists have no imagination at all. I want to make things far more wonderful than gold.”

Blüstav clicked his tongue in irritation. What was more wonderful than wealth? “Have you read Dorn’s Philosophia Speculativa?” he asked. “Or Ovid’s Metamorphoses? Have you read Zetzner’s Theatrum Chemicum?”

“No.”

“Then you will never be an alchemist,” said Blüstav. “It takes a lifetime of study, and you’re going to die in an hour.”

“Well,” said Teresa. “Why don’t you save our lives, then?”

“Impossible!” Blüstav declared, and Teresa shook her head in irritation, as if she disliked the word.

“Why is it impossible?” she asked. “Your alchemy could save us.”

“My alchemy? True, I could change these lead chains into gold ones,” Blüstav lied, “but what help would that be? We still couldn’t escape!”

“What if I saved us?” asked Teresa. “Then could I be your apprentice? You could teach me what Mr. Dorn and Mr. Ovid and Mr. Zetzner have to say.”

Blüstav sighed: this girl was a liar, a comedian, and a fool. He closed his eyes. “Some things you just can’t change. A death sentence is one of them.”

“Everything changes,” said Teresa. “I’ll show you.”

Then she began to experiment, mashing up moss and limestone with other ingredients lying around the cell; things Blüstav could no longer remember. In a few minutes Teresa had made a discovery.

“This should do it,” she muttered, smearing the paste over their shackles, which began to hiss and change.

As Blüstav watched in amazement, they turned green and sprouted yellow and white flowers. Binding his hands were no longer lead chains, but daisy chains.

“See?” said Teresa, ripping them off. “Easy. Now let’s do the same to the bars on that window!”

Half an hour later they were running down a muddy track, the shouting of the guards far behind. A breathless Blüstav knew two things: he was no longer going to die, and his new apprentice was already the greatest alchemist ever to have lived.

And he realized something else: she could make him a fortune.

When they got back to his laboratory, Blüstav showed Teresa around.

“There are three things all alchemists must have in their laboratory. Number one: shelves!”

“Why, Master Blüstav?” said Teresa.

“They are where you will neatly stack your alchemicals. Number two: a cauldron!”

“Why, Master Blüstav?”

“The cauldron is where you will mix your alchemicals. Finally, number three: a library of rare and mysterious books!”

“What do I do with those?”

“You sit there and look at them and think how clever they have made you.”

Then he gestured to the laboratory around him: to the stove and bellows, the water pump, the armchairs and the window. “Everything else,” he said, clapping his hands together, “is a luxury. Now! I am going to test you, Teresa. It is the same test my master gave me when I first became his apprentice. I want you to change that cauldron into . . .” Blüstav settled on the first thing that came into his mind. “Gold. A great, big pile of gold.”

“Why, Master Blüstav?”

What irritated Blüstav most about Teresa was that she asked so many questions. Particularly that short little one. It was such an easy question to ask, but it required him to make up the most complicated answers.

Because it will make me rich, he thought excitedly.

“Because it will teach you alchemy,” he said solemnly.

“But I already know how to make gold,” said Teresa. “It’s boring yellow stuff. Teach me something else.”

Blüstav gritted his teeth. He would have to find some other way to make his fortune from Teresa.

“Very well,” he said. “Turn the cauldron into a . . .”

His mind skipped through various possibilities: Chicken? Egg? Clock? Dressing gown? Lampshade?

“A boat,” he settled on eventually.

Teresa went over to the library of books, and studied the titles on the spines. “They’re all about making gold.”

Blüstav chuckled. Did she expect one to be called How to Change Cauldrons into Boats?

After a while Teresa walked away from the shelves.

Blüstav was disappointed. “At least have a go,” he said.

“I am,” said Teresa.

<

br /> She turned on the water pump, flooded the laboratory, and got in the cauldron.

“Finished,” she said. “The cauldron is now a boat.”

“That’s cheating!” said Blüstav, furious that Teresa had both outwitted him and got his feet wet.

“That’s using your imagination,” she corrected.

“Imagination has no place in the mind of an alchemist,” Blüstav declared.

Teresa sighed. “But, Master, alchemy happens in your head before it happens anywhere else.”

From that day, Blüstav began planning how to exploit Teresa. He wanted to trick her into making him rich, but she was too gifted, stubborn, and questioning just to turn lead into gold for him. Blüstav needed a lie more devious than any he had ever told before.

This was it: “Teresa! I am going to give you more tests: each one will be difficult in its own way. Trust in your master. Once you have completed all the tests, you will become the world’s greatest alchemist.”

However, beneath Blüstav’s lie was a plan: every alchemical potion Teresa made, he would sell to the rich and famous. It was the greatest lie of his life, and Teresa believed it totally.

So Blüstav traveled the world, talking to the rich and the powerful, and they told him their desires:

“I want a seven-fingered hand,” said a concert violinist in Edenborg. “I’ll pay you in gold.”

“I want diamonds on the soles of these shoes,” said the Duke of Madri. “I’ll pay you in silver.”

“I want flea lotion for my son,” said the Czar of Petrossia. “I’ll pay you in platinum.”

Teresa’s alchemy fulfilled their every wish, and in return, Blüstav took their gold and silver and platinum. His customers all agreed that truly, he was the Greatest Alchemist of his Age, and not one of them suspected that all the while it was his apprentice who worked his incredible alchemy.

The lie couldn’t last. Blüstav, obsessed by his fortune of gold and silver and platinum, didn’t notice Teresa changing. But she was. Every Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday, she would glance out the window to a patch of well-trodden grass below. She smiled for no reason at all. It was only when she started making mistakes, and Blüstav’s reputation as the Greatest Alchemist of his Age began to suffer, that he finally noticed what was happening.

“TERESA!”

“What, Master?”

“You gave the Prince of Baveria the legs of a scorpion and the tail of a horse!”

“Oh,” said Teresa. “Isn’t that what he wanted?”

“It was the other way around!” shouted Blüstav. “He’s got a very important war to fight and now even his own soldiers are laughing at him! You’ve just lost me a very important and incredibly wealthy customer!”

“Oh,” said Teresa. “Oh, well.”

Then she gave a long sigh and looked out the window.

“My goodness,” said Blüstav. “You’re in love!” It was so obvious now that he wondered how he hadn’t seen it before.

“That’s right,” said Teresa, showing him the ring. “And married too.”

“Married?” Blüstav yelled. “When? To whom?”

“At two o’clock this morning, to my husband,” said Teresa. “I can’t be your apprentice anymore, Master, I’m Mrs. Peppercorn now. I quit!”

Those two words terrified Blüstav. He froze, as if a lion had prowled into the room. If Teresa left, he’d lose everything! Fortune! Reputation! He pleaded and threatened; he called her names until he lost his voice.

“You haven’t completed all your tests!” he cried. “You’ll never be the Greatest Alchemist now! Stay, Teresa, your master commands it!”

But Teresa wouldn’t listen. Lies had no effect on her anymore: she was in love, and that was the truth.

Blüstav stared out of the window as she left, feeling numb.

And then a single thought formed in his mind: one day, he would have his revenge.

Time passed, and Blüstav sank into misery, poverty, and obscurity. His customers forgot him. He forgot the few bits of alchemy he had once known. He couldn’t create anything. He couldn’t even invent a decent plan of revenge.

Blüstav was sitting around in his laboratory, staring up at his shelves of alchemicals and books, waiting for inspiration, when it happened. There was a knock at the door.

“Is that you, Teresa?”

“It’s me!” she called through the letterbox. “I have lots of alchemy to do. Will you help?”

“Of course I will,” Blüstav lied. “What is it for?”

“It’s for my daughter, Lettie. It’s going to save her life.”

Blüstav felt himself filling up with jealousy. This was the first time Teresa had made something that wasn’t his.

“What is it?” he asked, and he knew before she told him that he wanted it.

“A new invention,” said Teresa. “Snow.”

Teresa needed a new laboratory—a cold place, away from dry land. So she and Blüstav sailed across the Channel, found an iceberg, and hollowed out a laboratory in the top, complete with cauldron. They painted all the walls with æther to keep in the cold.

“That’s the easy part,” Teresa told Blüstav. “Now the real work begins.”

Blüstav realized Teresa was in the middle of alchemy so complicated he didn’t even understand what it was she was changing, let alone why she was doing it. He slunk around the iceberg, little more than a servant, fetching whatever she asked. And all the while he waited for his chance.

A year passed as if it were a day. Teresa made a great silver wheel, and on it she spun a cloud. In great glass tubes the shape of bells she grew shining white ice.

One night as Teresa worked on her invention, Blüstav crept up to the laboratory and found her asleep from exhaustion. She had cut a length of silence one hundred years long into tiny moments, charged them with static and coated them with dust. She had sewn them inside a cloud, and thrown in six dice six times over. She had stirred in salt and æther. Above her head floated the nimbostratus, so nearly finished. Only one final ingredient remained.

Blüstav went to the recipe she held in her hand and gently took it from her grasp. He read the last instruction, for it was the only one he understood.

“ ‘Finally, add water,’ ” he murmured.

Teresa slept on, as he filled up a bucket and threw it into the cloud. He stepped back as the first snowflakes fell.

“Diamonds,” breathed Blüstav. “She’s found a way to turn water into diamonds.”

To him, this was more incredible than turning lead into gold. The greed inside him stirred again, like a hibernating beast after a long winter. He wanted the snow more than anything. And it was then that, lacking any imagination, Blüstav thought about stealing it. What else could he do? All his life he had been a thief. His palms itched, and suddenly he was holding a handful of the diamonds in his hand.

They melted away to water.

“It’s just water,” he said, crestfallen. He almost laughed: for the first time, Teresa had tricked him, and she had done it in her sleep.

Then Blüstav realized: if snow had fooled him, it could trick other people too. If he took the cloud, he could sell the snow as “diamonds,” then escape before they melted. It would be a lie that would give Blüstav both the fortune and the revenge he craved.

He didn’t stop to think about Teresa’s daughter, and why she needed snow to live.

With Teresa slumped over her desk, asleep, Blüstav packed the cloud inside a suitcase. He stuffed as many alchemicals as he could carry in his coat pockets, and crept out of the laboratory. Softly, he shut the doors, took several steps backward, and searched his pockets for one of the æther vials he had stolen.

He threw it, hard. A hundred drops of liquid frost burst upon the doors. They scattered over the hinges, the handles, the lock; the æther froze them shut in seconds. It would be a long, long time before they thawed.

Blüstav smiled at the thought of Teresa trapped in her laboratory. It

was fitting revenge for what she had done to him. He went down the stairs to the jetty and set off in the only rowboat for the shore.

He didn’t look back, not once.

The Distant Rising Smoke

“That was ten years ago,” said Blüstav. “Ever since then, I’ve traveled all over the world from city to city. I arrive, fill my customers up with æther, pretend to sell them diamonds . . . and vanish with their money before the snow melts.”

All through his story, Lettie’s hatred for Blüstav had been building up inside her like steam. He had stolen, tricked, and marooned Ma on an iceberg laboratory. He was the most deceitful and selfish person she had ever known.

And he didn’t even care!

“What made you come to me?” she growled.

Blüstav gave a greedy smile, but his eyes were troubled. This time Lettie read his gaze easily, seeing that same quickness in them as before. They were searching his head for a reply.

No, not a reply, thought Lettie. A lie. He’s looking for a lie to tell me.

And for a moment, that struck her as strange. But just then Blüstav found his lie:

“It was an experiment, I suppose.”

It wasn’t a very good lie, but he spoke it with such sincerity it made Lettie forget, at least for a while, the truth: Blüstav didn’t really know why he had brought snow to Lettie.

“Yes, an experiment. I thought you might unlock the secret of snow. After ten years I still don’t know what it really does, except melt. I thought perhaps the truth might make me even richer.”

“I see,” said Lettie, not really seeing.

“The mystery of snow was yours to solve. It was made for you, Lettie Peppercorn. Now it’s mine, but in the beginning, it was yours.”

“Well, now you can give it back!” Lettie shouted.

“Snow melts for you, the same as it melts for everyone else,” Blüstav said scornfully. “Why should I?”

Lettie didn’t have an answer. Why was she so special? How exactly could snow save her life? Only Ma knew. If only she was there! Lettie clenched her fists and jammed them in her coat. It was so frustrating. What were they supposed to do now?

The Last Zoo

The Last Zoo His Royal Whiskers

His Royal Whiskers Lilliput

Lilliput Hercufleas

Hercufleas The Adventures of Lettie Peppercorn

The Adventures of Lettie Peppercorn