- Home

- Sam Gayton

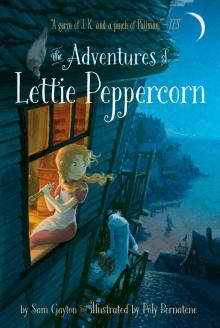

The Adventures of Lettie Peppercorn Page 15

The Adventures of Lettie Peppercorn Read online

Page 15

On the far side of the boat, Captain McNulty seemed to have exactly the same thought. He locked eyes with Lettie. Then both of them looked at the bazooka lying between them. Lettie staggered toward it as the deck seesawed under her feet. The crane cogs screamed and Noah roared and the bazooka lay silent, waiting to see who would claim it.

Lettie started off closest, but Captain McNulty had sea legs; the rocking of the boat had no effect on him. Her insides dropped as he strolled up to the bazooka and bent down to scoop it up.

But then there was a BANG, and his eyes bulged in agony. The Goggler, half-blind with pain, rage, and short-sightedness, had seen two blurs in front of her and fired her pistol.

Unfortunately for Captain McNulty, she had picked the wrong blur. The bullet whizzed straight through his boot. He howled and spat and swore and made one last grab for the bazooka, but Lettie whipped it away from his grasp. Hefting it in her hands, she aimed without thinking and squeezed the trigger.

The tiny dynamite stick flew from the barrel of the bazooka, landing at the foot of the crane. Blubber Johnson didn’t even notice it there as the fuse hissed away to nothing and the stick went . . .

BOOM!

The explosion threw up sparks and smoke, lifting the crane into the air as if it were a firework. Suddenly it was no longer attached to the Bloodbucket and Noah was no longer trapped. He saw his chance. Jerking his tail back, he flattened the crane with a heavy swat, stabbing it down through the Bloodbucket’s deck.

Never before in seafaring history had a whale harpooned a whaling ship. The crane pierced the hull, the sea came up like a fountain, and the whalers (those who were left) cried out, “Abandon ship!”

Grot-Nose Charlie ran for the lifeboat, holding his nose. Captain McNulty hopped after him. Stoker Pete came up from the engine rooms and dove into the waves headfirst, almost as if he was relieved to be finally having a wash. But Lettie did not watch them: she scoured the deck for Blüstav the clam.

The sea splattered and sprayed as it gobbled up the ship, spitting foam like saliva over Lettie’s feet. She began to panic. He wasn’t anywhere! There were floating barrels, harpoons, lifejackets, and Blubber Johnson’s boots . . . but no Blüstav. She only had a few minutes, and she couldn’t see him. Lettie froze in fear. What if he sank into the sea along with the ship? The cloud would be gone forever.

She caught a glimpse of something black, lodged between two crates at the sinking end of the ship. It was him! Dragging Blüstav free, she rolled him to where the deck was still dry. Her hands were shaking. His shell was as black as his coat had been, and Lettie ran her hands over it, feeling rough bumps and raised patches that had once been buttons and pockets. She had Blüstav, now she had to find a way to make him open and give back the snow he had stolen for so long. The crones hadn’t made him. Not even Ma had made him. How could Lettie?

She searched the littered deck for things to use. She tried prying him open with a rope and a pulley, but he stayed shut. And the water rose higher.

Lettie pressed her ear to his shell. She heard rumblings inside of him. She heard his fear and his greed. She began to whisper, but not to Blüstav. She spoke to the cloud.

“Hello, cloud. You’re angry, aren’t you? I can hear your rumbling. I’ve seen your thunder. You’re trapped. I know how that feels, cloud. I’ve been trapped just as long as you, you see.”

Underneath Blüstav’s shell, the cloud stopped its thunder. As if it was listening. Lettie surged on: “But we can help each other, cloud. We can set each other free. When you’re free in the sky, I’ll be free on the ground. I’ll never trap you, I’ll let you spread out across the world and make snow wherever you want. But you have to help me now. I can’t get you out all on my own.”

And Lettie heard the cloud start to rumble, and felt Blüstav start to shake, harder and harder.

“That’s it!” she shouted. “Struggle, cloud! Wriggle your way out! Work your way free! I know you can do it!”

And the cloud fought, fought to be free . . . And Lettie fought too, with every ounce of her strength, to force Blüstav open . . . And the cloud thundered and roared . . . And Lettie pulled and sweated and pulled, and finally, she felt Blüstav give in.

He opened an inch, and her hands trembled as he struggled to shut again. There was the snow cloud, squashed tightly behind his jaws like a pearl.

But now that Blüstav was open, it could escape: the cloud billowed away at last and rose into the air.

It looked different. It had spent so long swallowed up in Blüstav’s coat that it had turned pink.

Why pink? Lettie wondered.

And she realized just in time. Pink was the color of the gastromajus that Blüstav had swallowed! The cloud had soaked it up like a sponge, and now it was free, it was ready to spit it all out again.

Lettie Peppercorn, you get to shelter!

She dove to the ground as the cloud swept over her, dark and spitting, brewing up a blizzard. But this snowstorm would change anyone it touched; change them into their last meal!

Lettie ran for cover. The cloud rose above the deck. She had to get away before it snowed. She ran past the crones as the ship pitched and sank. There! Noah swam to her left, circling the Bloodbucket anxiously. She cried out to him and he sidled up, so she could jump on. A fat, pink snowflake drifted just by her foot as she leaped for his tree.

“The girl!” cried the Walrus.

“Never mind the girl,” said the Goggler. “Look at the cloud! It’s out! It’s out and right above our heads!”

The cloud thundered and swelled, full to bursting.

“Snow for us, cloud!” the Goggler cried. With her scopical glasses on, she would have spotted that the cloud was full of gastromajus in an instant. But she was blind, and the Walrus was stupid, so they raised their hands up to the peals of thunder and danced with jubilation.

“Snow!” they began to chant. “Snow! Snow! Snow!”

They were still chanting when the cloud split, covering them head to toe in a thick blanket of pink alchemicals.

Noah’s leaves shielded Lettie from harm, and she huddled around the trunk and watched the gastromajus tumble down onto the Goggler and the Walrus. Howling, screaming, they ran for cover but it was no use. They were in the midst of the blizzard, and the alchemy was working.

Lettie saw their faces turn gray and their hands become claws. She saw their eyes become black balls on stalks, their skin turn to shell. It was horrible to watch, but no more than they deserved. The old crones had become a pair of big, gray lobsters; they scuttled into the waves, sank to the bottom of the ocean, and were never seen by Lettie again. (They spent the rest of their days skulking among the muck of the sea floor, consumed by jealousy and meanness, evicting hermit crabs from their shells, until they were both caught in a fisherman’s trap and served at the wedding feast of Her Royal Highness Princess Josefin of Laplönd. Very bitter, tasteless, and gristly lobsters they were too, and many of the guests complained to Princess Josefin, who cried and stamped her feet and nearly executed the chef. But she spared his life and forgave him everything, for when he scrutinized the lobsters to see what was wrong he found five gold rings on the claw of one, and a chandelier earring hanging from the other.)

Lettie watched the Bloodbucket slipping away. With a last gurgle it was gone. The whalers, far off in the rowing boat, began the long journey back to land.

“Serves them right for what they did to your grandma,” said Lettie to Noah. “For what they tried to do to us.”

She felt no pity in her heart for those cruel and vicious men. They had learned a valuable lesson: never pick on whales, or small children—one day they’ll decide to fight back, and then you’ll be sorry.

“Let’s go home,” she said, reaching into her apron to touch Da. Noah turned and swam south toward land. Toward Albion and Barter.

And following them drifted the snow cloud. It had snowed away every last drop of gastromajus. It had thundered away its anger at being trapped

for ten years. Now it was a color Lettie had never seen it before. Now it was white.

The Awful Loneliness Returns

Noah swam for two days, with Lettie in his branches. He grew apples for her to eat, and when she became sick of apples, he grew pears. Lettie spent the daytime climbing and talking to Noah. She told him her whole life: about Periwinkle and Da and her home on stilts. At night she watched the stars if they were out. But sometimes the snow cloud was in the way, and then she had nothing but her thoughts of Ma.

Sometimes Lettie thought of Blüstav too, somewhere at the bottom of the sea, tossed by underwater currents. She couldn’t help feeling sorry for him, despite what he had done. He didn’t deserve to be a clam, down in the deeps, all alone.

She first knew they were nearing Barter when she saw Albion’s gray cliffs against the horizon. As Noah swam up, she could see the familiar shape of the valley and the first faint spires of the ships. Lettie sat watching the miniature town grow and grow, until at last Noah surged into the harbor. There were the cobbled roads and slate houses. Everything smudged a dirty gray or dull green. There were some traders selling fish on the quay. There was the smell of vinegar. There was the clippety-clop of hooves. A few children on the beach were staring. Many ships had come into the harbor, but never a whale.

Noah swam right up to the harborside, and stopped. He lowered his tree until Lettie could step lightly onto the shore. But she didn’t. She clung to him.

He waited. He shook his branches gently, but Lettie wouldn’t budge. In her heart was a feeling she hadn’t felt since leaving Barter: her loneliness had come back.

Because, after everything, Ma was still somewhere out there.

And Da was still a beer bottle.

And Noah was still a whale.

It was Noah who terrified her the most, because deep in her heart she knew what had to happen. He had to swim away, swim away and leave her. She could feel it in the silence between them like distance.

With Noah she had unlocked the secret of snow; the secrets of alchemy. With him, Lettie had shared everything: battles, escapes, starry nights, stories, and chili soup. If he left, she would have nothing. Her only friend would be the cloud above her head.

It was all the fault of stupid alchemy.

“Stupid stupid stupid,” she muttered. And then she shouted, so loud the fishermen jumped and ran from their stalls: “WHY CAN’T THINGS STAY THE SAME? My life was boring and sad but I’d gotten used to it. But then I got all hopeful that things were going to change for the better, and they haven’t, and now I think everything is just worse and I can’t take finding a family and a friend and then losing them all again.”

She sat in the tree and cried for a bit, feeling miserable and lonely.

“Oh, Noah,” she wept. “I want the old you. I want you back the way you were. I don’t want a whale for a friend. I don’t want a beer bottle for a da. I don’t want a ma made of air. I don’t want to be a stone. And you can’t say anything to make me feel better.”

Noah shifted uneasily in the water, and then he dove.

“And I don’t want to drown, either,” she said loudly, but he ignored her. She held on to the branches and took a deep breath.

As soon as her ears were under the water she heard him. He was singing, but it was unlike anything she had ever heard before. Noah’s whale song was strange and powerful and sad and beautiful. It made all the water buzz and shake around her. Listening to it, she felt she understood: Noah was sad to be leaving her, but he was saying thank you. He loved being a whale.

Then his singing stopped and they came back up. She gasped for breath as the water ran cold and freezing from the tree and the sun began slowly to dry her.

“Thank you too, Noah,” she said, wringing the water from her coat. She stepped from his branches. “I don’t know how you did it, but you’ve made me feel better, somehow.”

Noah shrugged his fins, as if to say: That’s what friends are for.

“I wonder how long my alchemy will last,” she said to him. “How long will I have to wait for you to become a boy again?”

Noah shrugged his fins again, as if to say: No alchemy lasts forever.

Realizing that made her feel even better. “You’ve cheered me up without saying a word!” she laughed. “Just how do you do it?”

He didn’t have to say it or sing it. Lettie just knew.

She asked two hundred and twelve times why he was leaving.

“And I’ll keep asking until I get an answer I’m satisfied with!” she said.

But, of course, he could never answer her, except in his strange underwater songs. By the water’s edge, she tried to make him stay. She told him:

“You’re my best friend.”

And, “You saved my life.”

And even, “You make better soup than me.”

But Noah was going, and that was that. There are some things that just belong to the sea—whales are one of them, and Noah was another. Splashing his tail in farewell, he turned and left the harbor. He swam away, his tree leaves turning green to gold and red. They blew off on the breeze.

“I’ll see you again, Noah!” she yelled. “Because no alchemy lasts forever! You won’t always be a whale, but we’ll always be friends, do you hear? I’ll see you one day soon!”

Lettie stood there, shouting and crying and waving. She told him she’d never forget him. Never, ever, ever forget him. It was all she could say and she said it again and again and after that, she just waved.

She waved at Noah, then she waved at the ripples he left, then she waved at the waves. And when there was nothing left to wave at, she turned back to the town.

A Top Hat Wishes to Be Borrowed

Lettie walked on through Barter as quickly as she could, all her thoughts on her petrifying feet. She even stepped on seaweed and fish heads rather than the cobbles. The wind was picking up, but it was no comfort anymore, just a cold nuisance. She held Da in her pocket, hidden away from any drunken sailors—she wasn’t having any of them drink him. But the streets were almost empty.

“Well, well,” said a voice from a doorway. “The landlady’s back.”

It was old Mr. Pity, the firewood seller. He was at the entrance of a tall, cozy-looking pub called the Bargaining Bess with his ax by his ankles. A steaming cup of khave sat in his hands, a fluffy gray beard sat on his chin, and a top hat sat on his head.

“That’s right,” said Lettie. “I’m back.”

“Wondered where you and your da had got to.”

“I went to sea. Da came too.”

“Hmm.” Mr. Pity stroked his beard and tapped his foot. “Seeking treasure were you?”

“Sort of. I was looking for my ma.”

“Ah,” said Mr. Pity, holding his hat as the wind blew fierce. “Find her?”

“Yes,” said Lettie. “But then she got lost again and my da is still a beer bottle, so I’m all on my own.”

Mr. Pity looked concerned. “Don’t you have any friends you could stay with?”

“My best friend lives in the sea.”

Mr. Pity sipped his khave thoughtfully. “What about your second-best friend?”

“He’s a pigeon.”

“Ah, pity.”

“He’s at home right now, I bet. I should go see him, Mr. Pity. If I stay on these stones too long, I’ll turn into one myself!”

“That’s a troubling thought!” said Mr. Pity, leaning farther from the doorway of the Bargaining Bess. “Well, my dear, if you ever get cold up in that house on stilts, you send me a message, and I’ll be up with some kindling for you, free of charge.”

Lettie waved and walked away. “Thank you! Good-bye! Stay warm!”

“You’re welcome!” called Mr. Pity fondly. “Adieu! You too!”

And as Lettie left, he doffed his top hat. Suddenly the Wind howled, then woompf ! It flew from his hands and landed in the gutter.

“Oh!” Mr. Pity cried as it slipped through his fingers.

“

I’ll get it,” said Lettie, running to pick it up.

“Psst.”

Lettie stopped. What was that noise? The Wind?

“Psst!”

Whatever it was, it was coming from inside the hat.

“Lettie!”

Lettie’s hand shot out and pinned the hat to the floor. Her heart was suddenly drumming in her chest. “Ma?”

“You got my top hat?” asked old Mr. Pity from the doorway. “Bring it here, miss.”

Lettie picked it up, covering the end as carefully as she could, and turned to show it to him.

“Hello,” said the hat.

Old Mr. Pity was about to sip his khave, but he jumped and tipped it into his beard instead.

“No need to jump,” said the hat. “I just wanted to let you know, I’m being borrowed.”

“Wha-what?” spluttered old Mr. Pity. “Why?”

“How do I know?” cried the hat. “I’m just a hat; I don’t decide how long someone wears me for! Are you mad, or just stupid?”

Old Mr. Pity looked at the hat with wonder. “I had no idea you could talk,” he said.

“Neither did I,” said the hat. “But then this girl comes along, and all I know is I need to be borrowed! Never been one to shirk my duty, me, so off I go! I’m needed.”

“But you won’t even fit her!” Mr. Pity protested. “Her head’s tiny!”

“Well!” sniffed the hat. “That is rude! You don’t hear me going on about the size of your head. Or your dandruff. Or the fact you’ve had the same haircut for fifty-seven years. Or the time you hid that ace of clubs underneath me so you could cheat at cards. Or the—”

Mr. Pity gave Lettie a look of utter helplessness. “Take it,” he said. “Take it.”

Lettie thanked him and began to walk away, but the hat kept on. “I’ll be back! Don’t you think I won’t be! But when I am, I want you to doff me to people in the street! And play cards fair! And hang me up on a hat stand with other hats! And get a haircut!”

The Last Zoo

The Last Zoo His Royal Whiskers

His Royal Whiskers Lilliput

Lilliput Hercufleas

Hercufleas The Adventures of Lettie Peppercorn

The Adventures of Lettie Peppercorn